On the evening of 15 August 1992, David Gant and a friend donned SCUBA gear and illegally entered Nickajack Cave in search of giant catfish. It was the beginning of an ordeal that would prove both nightmarish and miraculous for Gant.

Nickajack Dam is one of nine Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) hydroelectric dams on the Tennessee River. Completed in 1967, the 81'-high dam contains four hydroelectric units generating 104,000 kilowatts at capacity. Its 110'-600' lock system can lift up to nine barges at one time from Guntersville Lake, 41' below the dam.

Nickajack Lake, created above the dam, has 215 miles of winding shorelines along the beautiful Tennessee River Gorge, with its numerous coves and inlets providing 10,370 acres of surface area. The lake extends up the Tennessee River Valley 46 miles to the face of the Chickamauga Dam. The watershed providing drainage to the reservoir for Nickajack Lake is 21,900 square miles.

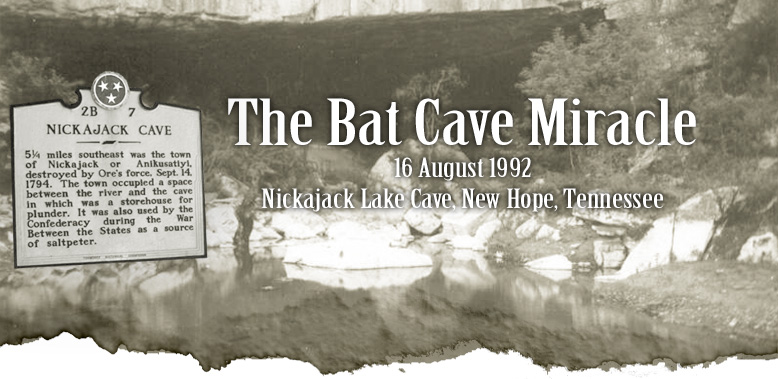

Nickajack Dam was named for nearby Nickajack Cave located about a mile east of the dam structure — one of thousands of cave systems in East Tennessee. Because the cave was to be flooded upon completion of the dam, it had been thoroughly surveyed in 1962 in order to ensure the lake water would not flow through the cave to a lower elevation.

Nickajack Lake is maintained between 633 and 635 feet above sea level. The ceiling heights in Nickajack cave average about 632 feet.

Each year, inevitably, open water SCUBA divers venture into underwater caves, and the results are usually tragic. There are many rules in cave diving, but two are paramount. You don't go into an underwater cave without the proper training and certification, and you don't go without the proper equipment, including a continuous guideline to the entrance. David Gant violated those rules.

Nickajack Cave had been known for centuries. Renegade Chickamauga Indians held war dances near the huge entrance as they plotted to resist the white settlers. To the Confederacy, the cave had been an important source of the saltpeter they used to make gunpowder. For a time, the cave had been commercialized. For years before and after that failed venture, its huge passageways had been a mecca for the adventurous. A huge stalagmite known as Mr. Big in the farthest reaches of the cave was said to be the largest in the world. But when the gates of TVA's Nickajack Dam closed, the water slowly rose to flood the cave. When the water had stopped, only fifteen feet of the entrance remained. A few hundred feet back in the passage, the ceiling descended and disappeared into the green waters of Lake Nickajack.

Since 1980, the cave had been protected by TVA as a sanctuary for the thousands of endangered Indiana bats which made it their home. A heavy chain-link fence blocked entry; a prominent sign told of the bats and the stiff penalties for violators. Further inside, a second fence waited for those who ignored the first.

Late on the night of Saturday, August 15, 1992, David Gant and a companion entered the water outside the fence. They knew it was forbidden to explore the cave — above water, at least. Underwater, they wouldn't be seen, and in fact they weren't likely to disturb the bats. Trained in open water diving, they had gone into the cave on three previous occasions. The night before, Gant had speared a tremendous catfish, which had fled back into the darkness. This trip would be an attempt to recover the trophy fish.

Visibility in the murky waters of the lake was about two feet, but Gant and his companion knew it would clear somewhat inside. As they descended, the beams of their dive lights disappeared into a greenish nothingness, then illuminated a muddy, rocky bottom.

Some time later, still seeing no sign of the fish, Gant checked his air gauge. Getting the attention of his partner, he signaled that it was time to surface. Together, they followed their bubbles upwards, expecting to emerge into the air filled portion of the cave...only to see a solid cave ceiling appear in their lights. They had wandered too far back into the cave into a no-mans land of completely flooded passages.

Rapidly exchanging signals, the pair dropped lower in the water and swam in the direction they thought to be out, then rose toward the surface. Again, the stark reality of the cavern ceiling confronted them. At that moment, the both men panicked. Their dive fins had stirred the siltation on the cave floor into a murky underwater fog, giving the two men near zero visibility. They separated. Gant's companion swam madly in one direction, Gant in another.

The companion was the more fortunate of the two, emerging into air-filled passage near the entrance with his tank nearly empty. Gant, having gone even deeper into the cave, surfaced alone in his solitary air pocket, completely cut off from the world above.

At 0200 Sunday morning, TVA security was notified by Gant's companion of the situation at Nickajack, and a rescue operation was initiated.

The call had initially gone out as a water rescue, and several dive rescue teams had responded. After evaluating the situation, and assuming that Gant would have died either from drowning, hypoxia asphyxiation in an air pocket had he been lucky enough to find one, or hypothermia, the Incident Commander (IC) of the lead dive team declared that this was a recovery operation (search for a body) rather than an active rescue (search for an living victim).

While highly skilled in open water search and rescue, none of the rescue divers were trained in cave diving. The nearest teams with that specialty were two hours away in Atlanta and Huntsville — add another hour or two for mustering those teams. Of the ten agencies and one-hundred plus operators who gathered at the entrance, there was not one person qualified to dive in the murky depths of Nickajack Cave.

At around 0600 Buddy Lane, Captain of the Hamilton County Cave/Cliff Rescue Team, was apprised of the incident. Buddy Lane, and his team, have more experience in cave rescue than any team in the United States — most likely any team in the world.

Knowing that the divers on the scene were not up to this specialized task of entering the cave, and assuming the best — that Gant might still be alive in an air pocket — Lane pleaded by telephone that trained caver divers be called in. This request was refused.

He asked that he, as a specialist in cave rescue, be allowed to come to the scene to assess the situation. (In the intense politics of rescue, a team must be invited to the scene by the IC of the lead agency.) His request was refused. This is a water rescue, the IC said, not a cave rescue. Refused permission to even approach the cave, Lane pleaded at regular intervals that cave divers be used. Each time, his request was denied by the IC, who also has a responsibility for the safety of all rescue teams, and did not want to further endanger any divers by sending them deep into the cave.

By dawn, the teams at Nickajack had made three dives into the cave's main cavern entrance — a 200 foot pool with an high ceiling where the bats roost. Using short reels of guideline, the divers had performed a circular search near the entrance, finding nothing. No sign of Gant, or response to repeated calls back into the cave hollows, and taps on air tanks.

Exhausted from the search, the divers were finally convinced they needed help. They agreed to allow cave divers be put in motion from Huntsville, 100 miles distant.

Member's of Gant's family had gathered behind a police line at the scene, holding a prayer vigil and praying hard for a miracle. As far as anyone could tell, none had been forthcoming.

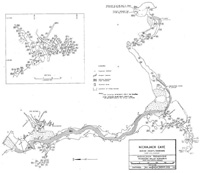

Click to enlarge.Meanwhile, Lane and his lieutenant Dennis Curry were on the telephone to the Tennessee Valley Authority. Just after sunrise on Sunday morning, they met with TVA representatives and obtained the detailed survey of the cave done before it was flooded. This map included vertical profiles showing the exact level of the water in various parts of the cave. Lane's suspicion was confirmed — it was apparent that there were air pockets in many places. While the depths of the cave were sealed by water above the 632 foot level, Lane and Curry now believed that Gant might well be alive, treading water in one of the air pockets where ceiling heights exceeded 632.

Still encountering resistance from the IC at Nickajack, Lane and Curry contacted Mark Caldwell, a National Defense Exec with FEMA who also volunteered his time as a state Emergency Services Coordinator (ESC) for the region. Caldwell lived in Chattanooga, and had extensive experience assisting Lane and Curry with HCRS operations in the tri-state area.

Knowing well how skilled Lane and Curry are, and trusting their judgment, Caldwell drove to the incident scene 45 minutes from his home. There, he was greeted at a mobile command post by the Incident Commander, who again insisted that the operation was a recovery not an active rescue, and provided his reasoning.

Caldwell, who was ideally suited to be an ESC because of his prior experience as a police officer, firefighter and EMT, understood that his role as an emergency services coordinator was to assist the "experts," not second-guess them. But he was confronted with a dilemma. He knew that Lane's and Curry's judgment in this matter was important. On the other hand, the incident commander had a great deal of experience in open water rescues.

Was Gant still alive? Should the lives of other rescuers be put at serious risk on the off chance Gant was alive?

As Caldwell contemplated his options, he decided that Lane and Curry were on the right track. Caldwell talked with Gant's family members, and was so moved by their prayers that he promised them that until he could establish that Gant was, in fact, deceased, he was going to have the IC treat the incident as an "active rescue."

Caldwell informed the IC of his decision to veto the "recovery" status of the operation, and called Lane and Curry to the scene.

Meanwhile, deep inside Nickajack cave, David Gant was certain he was going to die. For many hours — how many he could no longer say — he had been floating in darkness, keeping his head above water in a pocket of air only eight inches high, deep inside the flooded passages of Nickajack Cave. At first, blundering into this air pocket in the near zero visibility of the cave had seemed incredibly good luck. Now it seemed like a cruel joke. The air in the space around him, was running out. He could feel his breath coming faster as the level of carbon dioxide rose and oxygen declined. Hypoxia was taking its toll.

At the mobile incident command post, knowing that Gant's only hope for survival assumed he had found an air pocket, as Lane and Curry speculated, Caldwell determined that the only thing he could do to increase Gant's slim chance of survival was to have TVA open the generators and bypass spillways at nearby Nickajack Dam in order to lower the water level of the entire 46-mile lake system. This could possibly get some fresh air into Gant, and make access into the cave passages available without dive gear — meaning Curry and Lane could enter.

Caldwell weighed this decision heavily, knowing it would cost TVA hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost electrical generating capacity, but determined this action had to be taken. Amazingly, on a Sunday morning, Caldwell got through the TVA bureaucratic maze with just one call, and TVA system operators in Chattanooga responded immediately. Within an hour, Nickajack lake had dropped 14 inches — the maximum amount of drop allowed before navigation would be impeded on the river system.

TVA had moved 3,896,000,000 gallons of water in order to lower the lake from 633' to 631' 10". The movement of this mass of water to Guntersville Lake and the Raccoon Mountain Pump Storage lake, required TVA to adjust generating schedules for the entire system.

Caldwell ensured that TVA would hold the lake at that level until rescue operations were complete, and advised Curry and Lane, who were in route, of the circumstances. Lane was optimistic, recalling again all those ceiling passageway heights on TVA's survey maps were at 632'. They would have an air passage deep into the cave.

Caldwell requested that the IC support the active rescue effort and provide Lane and Curry, who had arrived on the scene, access into the cave entrance by boat. Indeed, the water level had dropped sufficiently to initiate a fast-water cave rescue, negating the need for SCUBA gear.

Using borrowed fins and normal caving gear, the Lane and Curry swam back into the cave. Both had a wealth of experience in wet caves, often pushing through passages flooded to within an inch or two of the ceiling. Here, with no more than two inches to breath, they made their way deep into the cave, spooked only by the very large fish, ("cave sharks" as Curry called them) which appeared occasionally in front of them.

"David Gant!" they shouted at intervals, the sound echoing weirdly against the myriad of passages. No answer.

"Hey!" Lane and Curry kept shouting as they entered each previously submerged passage. To their amazement, someone shouted back, "Hey" from deeper in the cave.

Gant was alive by a miracle of good timing and decision-making protocol. Just as the level of oxygen in his air pocket had diminished to a critical level, when he was scant moments away from losing consciousness, the water concealing the passage into his air pocket had dropped a crucial last fraction of an inch. As the water gently slapped the newly exposed ceiling, Gant had felt a sudden rush of cool air on his face. As he waited, regaining strength and hope, the flow of air grew stronger as the gap between ceiling and water slowly grew to an 1.5 inches.

Though the Nickajack Lake level had been dropped a maximum of 14 inches, it was only the last 1.5 inches that provided air into Gant, and passage for Curry and Lane to access him for the rescue.

Swimming toward Gant's shouts, Lane and Curry found that he was separated from them by a section of very low airspace. The two men popped out in front of Gant's astonished face, their lights blinding his eyes.

"You are angels!" Gant exclaimed, deadly serious, unsure whether he was seeing a hallucination or whether he was truly about to meet God. In the last moments of his 17-hour nightmare alone in the dark of that air passage, Gant had experienced a vision of two angels coming to take him home. He had visions of the divers searching futilely near the entrance and could see his family waiting and praying outside. He had seen two angels coming to escort him to heaven.

"Angels?" Curry responded. "We have been called a lot of things, but 'angels' is not one of them."

Gant was guided out through the low cave passages with those very real angels to a waiting boat, which would take him to the mouth of the cave and daylight he never thought he would see again. As he emerged from the cave, a wave of shouts "He's Alive!" spread down the banks of the river to the incident command post area and Gants family. It was a miraculous rescue and reunion.

"Found victim alive," the captain of the dive team wrote in his official report. "Everyone happy."

For his part, Gant was born-again as a Christian in the darkness of that cave. In the years that followed, he gave his testimony about the angels that saved him to congregations across the South — The Bat Cave Miracle.

"One could not have fictionally scripted the synthesis of so many events necessary for Gant's survival," Mark Caldwell said in an interview. The fact that Gant's dive partner actually got back to the entrance of the cave in order to get help; Gant's finding an air pocket that would keep him alive for 17 hours; the fact that Curry and Lane were contacted and located 1962 TVA survey maps on a Sunday morning thirty years later — maps which noted passage ceiling heights accurately; gaining access to the incident and, despite no evidence that Gant had survived, re-initiating an active rescue, even though by the time certified cave-diving teams would have arrive, Gant would have died; convincing TVA to drop the lake level to is minimum elevation — only the last inch of which got air and rescuers to Gant; all these things and more had to align perfectly for Gant to survive — and did.

Caldwell is man trained to make life and death decisions, to think in terms of probabilities, and make rational decisions based accordingly, but like Gant, he believes that God's hand was directing all the events that led to Gant's survival.

(Note: In 2007, National Geographic conducted interviews in order to feature this story in a special series called "Stranger than Fiction" scheduled to air in the Spring of 2008. Thanks to former HCRS caver Rodger Ling for his part in chronicling this story.)